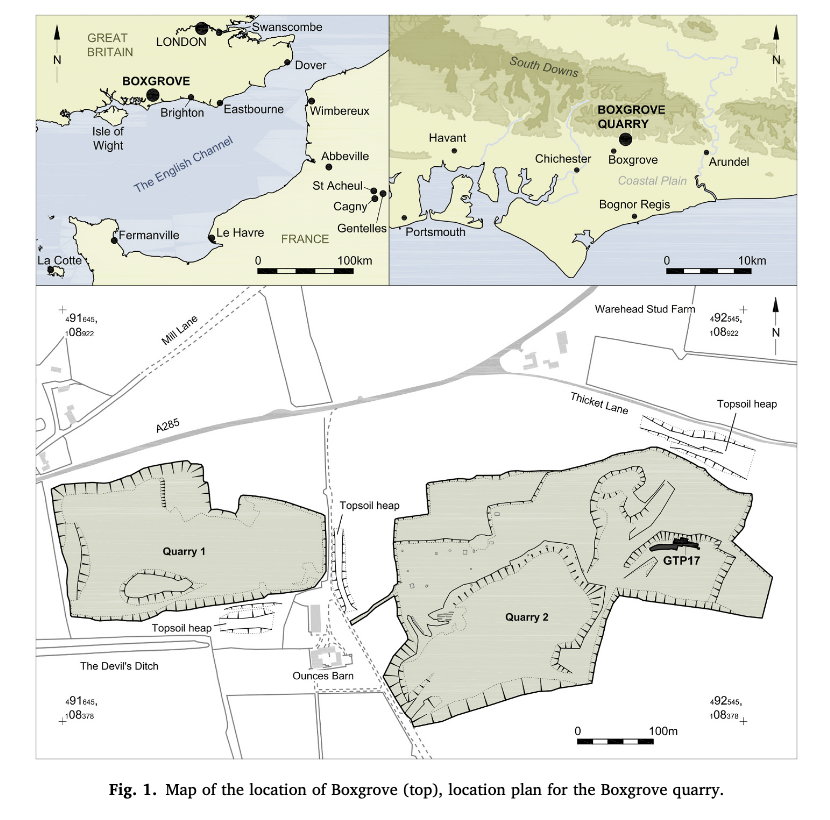

When I first began my PhD, I set out to understand early wooden weapons—not just what they looked like, but what they could do. Wooden spears rarely survive in the archaeological record, and discoveries of them have challenged our assumptions about the technological and hunting abilities of early humans. When I started my research journey, one prevalent narrative of early wooden spears was that they were unlikely to be effective hunting tools, and particularly as distance weapons. However, much of what underpinned that interpretation was anecdotal, or based on inconsistent research. Our latest paper, published in Quaternary International, is one piece of puzzling together empirical data on this question, representing an investigation into a fragment of a single horse scapula (shoulder blade) from Boxgrove, a Middle Pleistocene site in southern Britain dating to around 480,000 years ago.

A Famous Bone, a Big Question

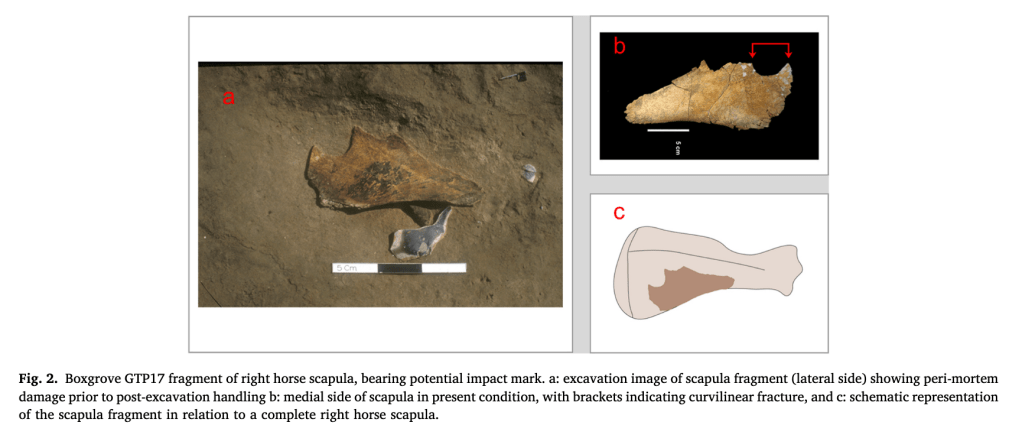

The Boxgrove site is one of the most important in Europe for understanding early humans. Excavations there have revealed beautifully preserved artefacts including stone tool knapping scatters and handaxes, butchered animal bones, and the earliest known hominin fossils in Britain. Among these finds was the remains of a butchered large female horse from a location nicknamed the Horse Butchery Site (known formally as Geological Test Pit 17, GTP17). Among the archaeological material that survived was a piece of the horse’s right scapula that is marked by a distinctive puncture, long thought to be the result of a spear impact.

For years, this scapula was cited as direct evidence of spear hunting half a million years ago. It featured in textbooks, lectures, and countless discussions about early hunting. The implication was that if the ‘wound’ represented smoking-gun evidence of a weapon impact, Boxgrove’s hominins were indisputably capable of tool-assisted big-game hunting.

But as our understanding of the earliest weaponry advanced, that interpretation began to raise questions. Could a wooden spear puncture a horse’s shoulder blade? Or might something else explain the damage?

Building a Multidisciplinary Investigation

This was where my PhD research came in. I wanted to test how early wooden spears actually performed when wielded by skilled weapon users, and whether they could replicate the type of damage seen on the Boxgrove scapula. To do that, I was lucky to meet some amazing collaborators, and undertake a series of experiments.

Initially, I could see in the literature that we lacked good quality data on spear performance that would allow me to set up experiments with a (relatively…!) appropriate balance of ‘realism’ and ‘control’ (both terms that always require careful use in experimental archaeology). To establish this, we first undertook spear thrusting and spear throwing experiments working with military personnel and javelin athletes, which enabled us to set parameters such as appropriate impact velocities. The spear thrusting experiments had further helped me understand that there is no good way of testing thrusting using machines (it’s too complex an action). So for the carcass experiments, we continued to use skilled humans for the thrusting experiment, while for replicating throwing spears we used an air cannon.

The experiments to test wooden spears’ ability to wound large prey took place at Cranfield Defence and Security, where we could safely and systematically test replicas of a Schöningen wooden spear against animal targets. We conducted both throwing and thrusting tests, tracking impact velocity, penetration depths, and damage to the bones. We also used flint cobbles to bash open scapulae, in order to replicate hominins accessing marrow and grease within bones, a behaviour that we already know the Boxgrove hominins were undertaking at the Horse Butchery Site.

We then compared the results to the marks on the Boxgrove scapula using a multi-analytical approach—combining microscopy, 3D imaging, and statistical comparison of damage metrics.

The Results: What the Scapula Really Tells Us

The findings were both exciting and surprising. The wooden spears, though effective weapons in their own right and capable of lethally wounding horses (which makes sense of the archaeological record…), produced little damage to bone, and what did occur was different to what we saw on the Boxgrove scapula. Despite repeated attempts, the spears couldn’t reproduce as large a perforation seen on the archaeological example, and nor did they damage thicker areas of horse scapulae.

In contrast, hammerstone impacts—when a stone tool was used to strike bone—created damage patterns that closely matched the archaeological example.

This suggests that the puncture wasn’t the result of hunting at all, but rather of butchery or marrow extraction. Previous publications have already clearly shown that the Boxgrove hominins butchered the carcass and were breaking bones in a way that is characteristic of access to marrow. Hammerstones and anvils at the site also lend support to this interpretation. Interestingly, in the course of the hammerstone experiment, we also discovered that horse marrow doesn’t have the consistency of, say, that of a cow. Instead it’s liquid, which along with the grease in the spongy bone, would make it accessible even in thinner bones like scapulae, that aren’t normally thought of as marrow-rich.

Rethinking Boxgrove’s Hunters

So, does this mean the Boxgrove people weren’t hunters? Not at all. In fact, the evidence from Boxgrove, including evidence that the carcass was secured early on and of wooden spear finds from the following two interglacials, still strongly supports the idea that these early humans were capable, weapon-using hunters.

What our study shows is simply that the scapula itself isn’t likely proof of that hunting event. It’s a different kind of evidence—one that speaks to what happened after the hunt, when the carcass was processed, shared, and consumed by a group working together 480,000 years ago. A recent re-investigation of the Horse Butchery Site proposed that the wider group, including youngsters, may have been present and actively engaging with the carcass using tools like simple flakes, while adults were making and using the sophisticated handaxes. This paper supports that interpretation: marrow and grease provide excellent sources of essential polyunsaturated fats, and would have provided members of the wider hominin group – including pregnant and lactating mothers and youngsters – with easy access to a highly calorific food.

That interpretation fits with the broader archaeological context at GTP17: a site rich with evidence of cooperative activity, systematic carcass processing, and technological sophistication.

Why It Matters

This project highlights the value of multidisciplinary science in archaeology. By combining expertise, we were able to test long-standing assumptions about early weapon use.

It also reminds us that scientific progress often involves correcting as well as discovering. The Boxgrove scapula has long been iconic, but that doesn’t mean its story can’t evolve. By revisiting old evidence with new tools, we can refine our understanding of early human behavior—and appreciate just how complex and capable our ancestors were.

Reflections on Collaboration

One of the most rewarding aspects of this work was the sheer diversity of people involved. Reconstructing how early humans hunted and butchered animals isn’t a task for a single individual—it’s a conversation between many.

From the ballistics engineers who helped set up the experimental protocols, to the martial artists and athletes who physically tested spear dynamics, to the veterinary mortician whose understanding of the anatomy of the horse helped us interpret what constituted a ‘lethal’ impact, to statistical approaches and microscopy: many people brought a unique perspective.

And, of course, none of this could have happened without the generous spirit of collaboration—people willing to spend their time to understand how to use a replica wooden spear, to operate high speed cameras, use hammerstones to bash bones, and peer down microscopes, all in the name of understanding the deep human past.

Looking Forward

This study is the final part of a broader series of papers from my PhD exploring the use of the earliest wooden weapons. Together, these studies aim to move away from anecdotal interpretations in order to build a more realistic picture of how early humans interacted with their environment, used tools, and worked together.

As we continue to both discover and reinterpret artefacts like those from Boxgrove, I’m reminded that archaeology is as much about people as it is about objects. The marks on a bone, the polish on a tool, the pattern of a scatter of flakes—each offers a window into the ingenuity and cooperation that define what it means to be human.

Read More

If you’d like to explore the full study, it’s available open-access here:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040618225003386

To read some other recent publications on Boxgrove see here:

Lockey, A. L. et al. 2022. Comparing the Boxgrove and Atapuerca (Sima de los Huesos) human fossils: Do they represent distinct paleodemes? Journal of Human Evolution 172, 103253. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248422001130

With thanks to the original excavation team, all the subsequent research on Boxgrove underpinning this study, those who supported the research through funding (AHRC, UCL, experiment.com), those who read and reviewed the paper in its various stages, and of course my co-authors and collaborators for their insights, expertise, and good humour throughout this project—and of course to the Boxgrove hominins and horse, who continue to teach us lessons from nearly half a million years ago.